|

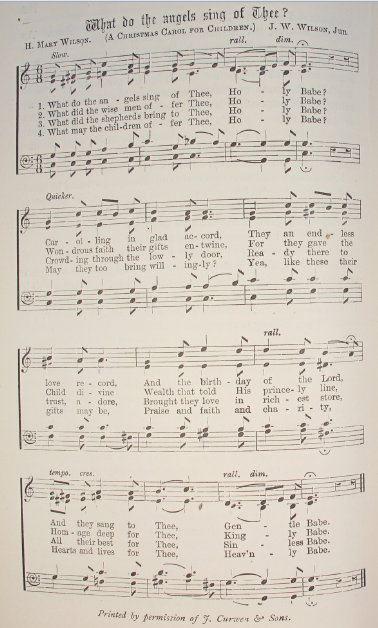

The Parents' ReviewA Monthly Magazine of Home-Training and Culture"Education is an atmosphere, a discipline, a life." ______________________________________ Greetingsby The Editor [Charlotte Mason] The Parent's Review carries loving Christmas greetings to all the families, scattered widely over the world, where it is a welcome visitor. It is rather overpowering to think of the thousands of beautiful English homes where these words will be read and accepted with more than Christmas goodwill. For we of the Parents' Review, we who write and we who read, are beginning to feel a more and more close bond of fellowship. Some of us have met in the flesh, and the meeting is always unusually cordial and intimate. Some of us as yet are only en rapport in the spirit, but the relation between us is none the less real and vital for that. There is a sort of freemasonry among us. We recognize each other by certain indubitable signs. At once we plunge into real heart-talk, and the weather and the gossip of the day are passed by as topics foreign to our thought. A zealous young ex-student of the House of Education listened, involuntarily, to the talk of two ladies at the door of the compartment in which she was traveling. Her heart burned within her, for they talked of Education, and on our lines. She laid little plans as to whether she would be able to get into conversation with the lady who was to be her fellow traveler, and tell her all about the Parents' National Educational Union, but, behold, before she had mustered courage to speak, the familiar red cover was produced by the lady, and it proved an open sesame. There was no difficulty about mutual outpourings after that. Perhaps we all feel that what a dear little girl calls the "Angel Book" (from the figure on the cover) is a sufficient letter of introduction. We know something, at any rate, of the aspirations of any chance acquaintance in whose hands we find it. It is a badge of membership. This is all very pleasant and very helpful, but, like most pleasant things, it brings its own responsibilities. The discovery of every new relation in life is also the discovery of new responsibilities, and it is time that the thousands of "us," who are in the van of educational thought, should perceive that we carry in our hands a gospel for the world, that gospel of Education, in the wide sense of the formation of character, which is, perhaps, the special evolution belonging to our day of the Gospel of Christ. "Behold the handmaid of the Lord" is the attitude proper for that beneficent angel whom men call Education, and the time is coming when the world will recognize that our Lord's binding precepts for the up-bringing of children are among the first of His commandments. Another glorious society [Report of the National Society of Prevention of Cruelty to Children, 1893, entitled The World of Forgotten Children, Central Office, 7, Harper Street, London, W.C.] has made it its business to see that no child shall be maltreated bodily. The report of this society is heart-sickening as shewing the fearful and horrible cruelty possible to the hearts of parents: the piteous unnameable distresses inflicted upon children already, 85,000 little ones have been brought under the sheltering and healing wing of the society, and Mr. Benjamin Waugh, the true "Children's Man," has succeeded in carrying, what he rightly calls, the Children's Charter, giving to the children all the rights of legal protection which hitherto, strange to say, have been enjoyed solely by the adult; the law of the land, having, no doubt, been framed under the somewhat sentimental notion, that a parent is naturally and necessarily a wise and loving person, devoted to the interests of his children, instructed, too, by nature in all manner of knowledge and moral rectitude proper for their well-being. Alas, we find that we have been living in a fool's paradise, that there is no degree of fiendish cruelty which is not possible to parents even in the so-called educated and wealthy classes. The records in the newspapers (and not a tithe of a hundredth of the cruelties discovered by this society find their way into the papers) fill us with shame and an awful sense that anything is possible. "Lord, is it I," we say within ourselves, and an overwhelming conviction that we are not wholly free from blame in this matter comes home to us all in proportion as our minds are awakened to the possibilities of education and to our own responsibility. It well for us all that a strong and noble society should have taken off our shoulders the anxious physical care of the "world of forgotten children," asking only for the funds for a campaign which many of us are only too glad to help forward in this way. But there are ways of despising, and hindering, the children which have not yet come under the world's category as cruelties. As yet, the world does not think that the child who is suffered to grow up greedy, sullen, willful, disobedient, is cruelly treated, so long as he is well-fed, well-clothed, and sheltered in a luxurious home; and yet there is more hope for one of these rescued little ones, however emaciated and forlorn, than there is for the spoiled child; spoiled, as an article of dress or ornament is spoiled, never to be of its full use and beauty any more. Mr. Waugh finds that the thing to do, in a given town, is to awaken public sentiment, correct public opinion, by forming a branch of his society there. The strength of public opinion is well-illustrated by the agonized cry of the wretched woman who found herself in the dock the other day "Oh my God, they look worse than they did yesterday," she cried, when the unhappy little beings who call her mother were brought into court: i.e., her eyes were opened by the force of public opinion, and she saw her work as others see it. Now, this is precisely the work that the Parent's National Educational Union is divinely called to do. It is not for nothing that we are in the van of educational thought. 'How the world is to be peopled is not my concern and needs not to be yours,' says the prince in Rasselas. But such sublime indifference to 'those others' is neither lawful nor expedient. It is most absolutely and certainly our business to see that the light we possess ourselves shall not be hid under a bushel but set on a candlestick. Now, in the nature of the case, we cannot go about holding up our light in this matter as private individuals. We may indeed show the world a family of well brought up children, and, no doubt, that is an illuminating influence; but to see that beautiful and delightful product of many efforts and many prayers, a good and simple child, no more shows other parents how to do likewise than would the display of a watch instruct us how to make one. Here is a case where we can do little or nothing for our neighbours individually, but, with the Society at our back, whose principles we can proclaim, whose methods we can advocate without any risk of being offensive to our neighbours, there is simply no limit to the help we can give. The full comprehension of our principles is necessarily slow work, because this is, in itself, a very advanced and liberal education; but, sympathy with our efforts, desire to follow our principles and unite with us in our labours, why, we have only to try, to learn how extraordinary is the response we shall meet with if we make ever so slight efforts in this direction. For example, a fortnight ago a lady offered her services to help in forming a Branch, expressing her willingness to act as secretary should her services be acceptable. Her offer was gladly hailed. She seized an opportunity to gather a few friends to hear an address from one of our most active and inspiring members. She could only give a day's notice; some of the people she asked were engaged, some were shut up by the damp, some were selling at a great bazaar. Only thirteen came, but out of thirteen, ten joined at once. This is the sort of encouragement that awaits any who will give themselves heart and soul to this great work. There should be a Branch in every town in England, and every county should have its own honorary secretary. Will any offer themselves for the work of secretary either for town or country? There is probably no good work quite so easy, quite so delightful, or quite so wholesome in its effect on one's own personal character. Nothing is easier than to begin the work. write to either of the Hon. Secretaries, Mr. Perrin [H. Perrin, Esq., 8, Carlton Hill, London, N.W. Miss Mason, House of Education, Ambleside. A.T. Schofield, Esq., M.D., 141, Westbourne Terrace, S.W.], or the Editor, or to our most earnest and able Chairman of Committee, Dr. Schofield, for instructions, papers, &c. Get up a drawing-room meeting, large or small. Get some friend of the work to speak, or, failing that, some lady or gentleman of local weight to read the more inspiring and instructive parts of our reports, and to speak to the resolution--"That a Branch of the Parents' National Educational Union shall be formed at--." At the close of the meeting, invite members to join. Form a little committee, etc., according to instructions, and with surprisingly little effort and in a very short time a branch of the Union will be in full swing, and every year will mark some new departure of great use and interest to both parents and children. We have not space for more now than an urgent appeal to our friends to take heed to our entreaties in this matter, unless it be to beg all subscribers to the Parents' Review to send in their names and subscription (5s.) to Mr. Perrin, and thus to become members of the Union, pledged to advocate its principles, whether or no they are able immediately to form or join a branch. What these principles are in extenso, all our readers know pretty well, but we hope to print them in a short form in next month's issue. In the meantime Mr. Henry Perrin will, we know, be delighted to send copies of our rules and principles to any who write to him for them (with stamped envelope.) Let us end as we began, with loving Christmas greetings to the parents and the children in all the homes which the Parents' Review reaches. May you have indeed a "Happy Christmas." "It is a comely fashion to be glad." May we venture to add that gaiety of heart is not merely a wayside weed that springs of its own accord, where it is not even wanted; but is a choice plant, not quite easy to rear, tender and delicate as it is lovely; a plant one must strike with the psalmist's hearty resolution "I will be glad," and then must shelter assiduously from the damp chill of every self-regardful feeling. Gaiety (not of occasion, but of heart) thrives only in an atmosphere of light and love. Farewell, dear friends, keep us and our work in remembrance on your "Happy Christmas." _________________ Parents Review Vol. 4 1893/4 pg760 What do the Angels Sing of Thee? H. Mary Wilson. What do the angels sing of Thee, Holy Babe? What did the wise men offer Thee, Holy Babe? What did the shepherds bring to Thee, Holy Babe? What may the children offer Thee, Holy Babe?  Proofread by LNL, May 2021  |

| Top | Copyright © 2002-2021 AmblesideOnline. All rights reserved. Use of these resources subject to the terms of our License Agreement. | Home |