|

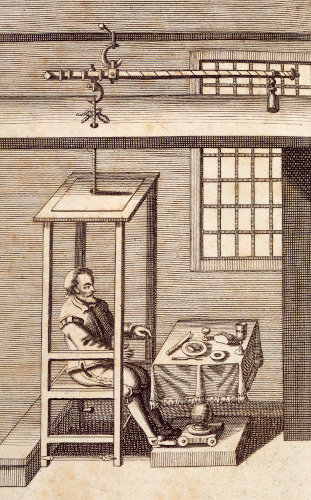

The Parents' ReviewA Monthly Magazine of Home-Training and Culture"Education is an atmosphere, a discipline, a life." ______________________________________ Self-Control.by H. Laing Gordon, M.D. (Read before the Harrow branch of the P.N.E.U., March, 1899.) I have been led to choose the subject of self-control for our consideration to-day, because of the suggestion that thoughtful parents sometimes tend to kill, with much cherishing, the qualities they desire to see established in their children. I shall endeavour to show that in every healthy child, there exists the mechanism by which self-control operates; and that it is by use that this mechanism is strengthened and the power developed. It cannot be denied that a well-balanced power of self-control is a valuable weapon in the battle of life. Although the men who have exhibited perfect self-control in every direction may be almost counted on one's fingers, those who attain eminence in various walks of life display the characteristic in one or more directions. The great diplomatist is generally believed to be capable of concealing his own feelings and designs while endeavouring to discover those of his opponent. The ideal judge listens to both sides with equal patience, and by neither word nor action prematurely displays a bias. The schoolmaster struggles with childish ignorance and curbs his irritation in a proper faith that understanding will come. While, according to George Eliot, a very necessary accomplishment of the medical man is that of being able to listen with becoming gravity to whatever nonsense may be talked to him. In everyday life all of us--whatever our rank or profession--require to exert ourselves to check the desire to tell other people exactly what we think of them. Impulsive outspoken people seldom attain eminence. But self-control is something more than a mere means of getting on; it is of course a priceless possession to the physical and moral natures. It may be well to clear the ground of the bogey of heredity which, as a rule, stands in a threatening attitude over a discussion of any such subject. I well remember one friend of student days--the time when one discusses and settles most of the questions of life with a zeal which would be ridiculous if it were not so earnest--who used to argue that, because his parents lacked moral backbone, he was doomed to degeneration; that no power could make up for his hereditary want of moral self-control. Happily, modern Darwinism has overthrown such miserably fatalistic doctrines; most of us now believe that, although inborn characteristics may be transmitted to our offspring, acquired characteristics are not so transmitted. And we may comfort ourselves that self-control is an acquired characteristic; acquired by greater or lesser use of the machinery which we all possess, and of which we ourselves are the only masters. Hence, even the child of parents lacking self-control may come to exhibit that power, if his environment is suitable. It will be well first to examine the nature of the mechanism of self-control. To help to an understanding, let us briefly recall the physiology of a well-known nerve-mechanism. Many of the functions of the body are carried out by a process called reflex action. This reflex action simply means that a sensory message is conveyed to a nerve-centre which sets up the appropriate motor-action. Thus, if the sole of the foot be tickled, a sensory-message is conveyed to the nerve cells in the spinal cord whence a rapid message is sent down the motor nerves, causing the foot to be drawn away. Or, again, if the eye be touched by a finger, a sensation is at once led by the sensory nerve to the nerve centre concerned, and the motor nerve which runs to the eyelid is stimulated from that centre, so that the eyelid is quickly closed. You also know that you are able by a voluntary effort to prevent the foot from moving when it is tickled, or to prevent the eyelid from closing when the eyeball is touched. To explain this preventive action we imagine the existence of certain higher nerve centres which have been called inhibitory centres. From one of these, a message is sent to the lower centre which prevents it from setting up the motor act of moving the foot or closing the eyelid. This mechanism of inhibition controls many of our vital functions in a manner of which we are unconscious; but our concern to-day is only with voluntary inhibition. Let us look for a moment at another bodily manifestation of reflex action more complicated than those already referred to. When the stomach is empty certain sensory nerves convey an impression to a brain-centre wherein the sensation of hunger is set up. This centre at once sends out a message by the nerves belonging to the muscles concerned in grasping and conveying food to the mouth, so that hunger is satisfied. But, although hunger is present and food is at hand, it may not be right to eat at the time the centre is stimulated. Hence a message is sent from our higher inhibitory centre which bids the lower centre delay before it sets up the appropriate motor action which results in eating. When the proper moment arrives, the inhibitory influence is removed to the gratification of the appetite. But our inhibitory centre may be weak; hence after a feeble struggle we eat what is on the table before the gong has sounded or grace has been said, and we are pronounced greedy. Or, again, the hunger may be violent and overcome the efforts of the inhibitory centre. Or the inhibition may be conquered in another way. Our friends may keep us waiting for the meal, the savoury smell of the food reaches us in wave after wave, perhaps we cast little longing looks at the smoking dish before us until at last the sum of these little stimuli exceeds the sum of the inhibitory influence, and there is nothing left for us but to sit down and eat in obedience to our appetite. This is really a physiological process known as the summation of stimuli. It is analogously illustrated every day in a familiar manner. A beggar runs after us asking in a low monotonous tone for a penny; we first pay no attention, then we feebly tell him to go away; but he understands mental physiology and persists; gradually his summated stimuli overcome our voluntary inhibitory effort and we are prompted to the motor action of putting our hands in our pockets and satisfying his desire. Or again, although we may inwardly abhor the modern craze for advertisement and pay no attention to one single poster in the street, the summated stimuli of "Quack's Pills" or "Boiler's Soap" repeated in station after station, in field after field, on pillar and post, arouse us to interest at last and may lead us to become purchasers of the advertised article. Every sensation has its appropriate motor result. Thus the motor outcome of the sensation of hunger is to eat. If we do not eat when the sensation bids us, we starve. On the other hand, if we go on eating to excess, we first suffer from what the ancients called surfeit, and finally die of repletion! The ancient method of avoiding the evil results of over-eating was to induce vomiting in a regular and business-like manner. Hippocrates, the Father of Medicine, himself taught that, in any case, it was a good thing to have a vomit once a fortnight. Most of us prefer, however, to bring our inhibitory centres into play, to stop the act of eating; and we do it almost without a voluntary effort. This is not brought about without education; we all know that an infant will often overfeed until its body is trained by experience to moderation. Thus, it is manifest that voluntary inhibition of physical processes is a habit. Some of us have a liberally trained habit in the matter of eating, and have bodies accustomed through education to receive more food than those whose inhibitory centres have been chastened. You know that the trappist monks are able to exist during seven months of the year on only one meal in twenty-four hours. I have here a photograph of a quaint old engraving in my possession, of one Sanctorius, who was so careful of his stomach that he sat in a balance during dinner, and as soon as the scale landed him on the floor he tabled his knife and fork and would not touch another morsel. This worthy man made the balance his inhibitory centre, and it is painful to think what may have happened when the balance got out of order, or he accepted an invitation to dine out. Parents should not neglect to help their children to depend on their own inhibitory centres in the matter of eating and drinking.  We have arrived, then, at the conclusion that voluntary inhibition of physical process is a habit. The physical processes to which we refer are in themselves habits--habits of body. Hence we may say that voluntary inhibition is the habit of controlling ordinary habits; voluntary inhibition is self-control. Therefore self-control is the habit of controlling habit. This somewhat free definition applies to habits of body, to habits of mind and to moral habits. The formation of habit is one of the cardinal principles of the P.N.E.U., and I will not weary you with more than a little on the subject. Physical habits, in a broad and popular sense, are little more than reflex actions; mental and moral habits are the same. Habit is, then, the association of a sensory stimulus or an idea with a certain motor act. For example, the sight (sensory stimulus) of a particular written note of music causes the child to strike the corresponding note on the piano; this habit, as you know, is developed by education, and although at first laboured, ultimately becomes rapidly automatic. Similarly when one says good-night to a child of good habit, he automatically begins to go to bed; if he is of bad habit he objects and may cry, especially if he has been allowed to dally on one occasion and has been peremptorily ordered off on another; the child who responds cheerfully to the idea that it is time for bed--and the idea ought not to be suggested if it is not meant--has developed inhibitory centres which check his childish desire to go on playing indefinitely, and has laid one foundation-stone of self-control. We all know the familiar instance of the value of our inhibitory centres in enabling us to check the natural desire to remain in bed in the morning. The ideal operation of the mechanism of self-control may be described as follows. A certain habit is in course of operation, the idea or sensory stimulus having set up the appropriate action; but a point is reached when either the action must stop or evil results will follow; at this point the inhibitory centres receive a message from the centre operating the habit, and they at once send down to that centre a message which causes the operation to cease--self-control is automatically brought into play. If self-control is a habit, it is obvious that it is developed and increased by exercise. This is a property of habits with which you are familiar. The more our self-control is exercised, the stronger it does become, the more powerful by use do our inhibitory centres grow. Therefore our aim should be to obtain a mastery of ourselves by full development of our powers of inhibition. Such is the weakness of human nature however, that although we may have perfect control over ourselves in ninety-nine directions we fail in the hundredth. It may be said that for every new habit, we require to develop a new inhibitory centre, so that in this, as in every particular of human life, our education is always proceeding. Self-control is one of the foundation stones of morality; but it is conglomerate, and made up of numerous elements. "Self-knowledge, self-reverence, self-control, these three alone lead life to sovereign power." [Tennyson] The power conferred by self-control is no unconscious power. The man who is master of himself is conscious of the fact and walks with an erect head through life. It is impossible for him not to be a man of character, and it is impossible for him not to shew his character. "It is as easy for the strong man to be strong as for the weak to be weak." Self-control brings us self-reliance. Helps us to say, "I think," "I am," in the face of the world. I commend to those who do not know it Emerson's essay on "Self-reliance." "What I must do," he says "is all that concerns me, not what the people think. This rule, equally arduous in actual and in intellectual life, may serve for the whole distinction between greatness and meanness. It is the harder because you will always find those who think they know what is your duty better than you know it. It is easy in the world to live after the world's opinion, it is easy in solitude to live after your own; but the great man is he who in the midst of the crowd keeps with perfect sweetness the independence of solitude." The self-reliant man has conquered another bogey besides that of the fear of non-conformity. "A foolish consistency," says the same writer, "is the hobgoblin of little minds. With consistency a great mind has simply nothing to do. He may as well concern himself with his shadow on the wall. Ah, so you shall be sure to be misunderstood! Is it so bad then to be misunderstood? Pythagoras was misunderstood, and Socrates, and Jesus, and Luther, and Copernicus, and Galileo, and Newton, and every pure and wise spirit that ever took flesh. To be great is to be misunderstood." Self-control teaches us to say "valiant noes" when others would have said "ruinous yeas." Psychologists speak of self-control as being sometimes stimulative as well as inhibitive. For the sake of simplicity I have regarded only the inhibitive process; on consideration you will realise the nature of the stimulative process. It is also usual to speak of self-control as applied first to action, second to feelings, and third to thought. For our general purpose to-day, it is not necessary to consider these divisions. But I may remind you how much more difficult it is to control the feelings than the actions. It is scarcely necessary to draw your attention to the dependence of self-control upon the mental powers of memory and reason. Let us now look once more at the practical aspects of our subject. I have of course no patent system for developing self-control as part of the child's unconscious life. Although I have argued on more or less scientific lines, I do not presume to say that this habit is to be established by rigid adherence to scientific rules--far from it! I desire to see self-control exercised in early youth pari passu with lower habits; and not left, as some authorities tell us it must be, to "develop" last of all our moral "faculties"; and I desire to see it grow in the child by pleasurable exercise, that in adult life he may look back and see that that which others struggle to attain has in him grown almost unknown. Each child must be treated according to its needs; not only may one child be born with a greater capacity for the development of the characteristic than another, but accidental early environment may perhaps have facilitated or on the other hand impeded the desired development. Our object is to allow the child to act, feel, and think for himself and control his actions, feelings and thoughts for himself. The control of the actions comes first, that of the feelings follows closely, while the thoughts are the last. We may help by exercising memory and reason, and we may endeavour to leave the child to find out for himself very often the advantages of self-control. Suggestion is, of course, a powerful influence and the suggestions conveyed by our own efforts in self-control carry their lesson for the child; hence we endeavour to set a good example, depending for its good result upon the child's great power of imitation. By this means we may lay, unconsciously to the child, the foundations of this powerful moral habit. For example, if a child is accustomed to see a servant prying into his father's papers, etc., when he is out, or his nurse reading his mother's letters, we need not be surprised if as a schoolboy he cribs from his neighbour. But precept is by no means to be neglected, and a great deal may be done by a word when we recognize that the child's powers are being tested by experience. It is a question well worthy of your further consideration whether it is always wise to keep from a child everything that may be harmful. It is urged by some that a child learns the advantage of good moral habits by first discovering the disadvantages of bad ones; that he learns to speak the truth by finding out experimentally how bad it is to tell a lie. But it requires a child with a phenomenal inborn moral power to thus early touch pitch and not be defiled. And I suggest that the average child is better for having the desire for every kind of good laid in him as early as possible, so that he may have a strong tendency thereto to give him strength when sooner or later he meets what is harmful or evil, as of necessity he must. And, remembering that self-control is practically always an acquired characteristic, I think my suggestion is correct. The child that is brought up to feel that "we needs must love the highest when we see it" may be safely left to fight his own battles. But the foundations of self-control may, like many other habits, be acquired by the child in the first few years of his life at home; when the time comes for going to school this foundation ought to have been already solidly laid. It is obvious that for the building of the superstructure we look to the youth himself and cannot disregard the effect of environment upon him, the influence of ourselves, the parents, of his teachers and his companions, and of all the other surroundings which affect him perhaps unconsciously only by proximity. Companions for our children before school days should be carefully selected for them; and we may often be guided by our knowledge of the character of their parents. Afterwards, let the child alone to select for himself, but watch. Again, I do not personally think that sufficient attention is always paid by parents to the character of the master or mistress to whom they resign their children at an early period. I myself know a preparatory school where practically every boy--day boy and boarder--bears more or less the imprint of the headmaster's influence, happily a manly and upright one. It is easy to understand how a contrary influence may have an unfortunate effect. The teacher's personality is of importance, not only in regard to his example and precept in the control of actions and feelings, but also in regard to the more professional function of teaching the control of thought. Many of us, for example, can remember teachers who were very far from helping us to efforts of concentration and attention, and whose methods have left us a distaste instead of a love for the acquirement of their particular lines of knowledge; while others rivetted our attention and kindled our enthusiasm. I speak here in Harrow with some diffidence; you probably all know more about this particular subject that I do. One practical point, however, I may refer to--the curious custom of sending a boy to a certain public school for no other reason than that the parent before him went to the same school. The masters, particularly the head, may be of quite a different stamp from those who turned out the father, and the result is often unsatisfactory, although of course not necessarily. A recent correspondence in The Times on the "Training of Teachers" was curious reading. No doubt it was read, marked, learned and digested by many parents. It is to be regretted that no parent, as such, took a part in it. I should like also to enter a protest against the custom of sending out moral failures to the Colonies. It is merely putting out of sight that which we do not care to face and for which we are probably ourselves responsible. It may succeed, however, and I have seen it succeed occasionally in youths, in adults never. By chance the youth may find a better environment abroad than he had at home, and the stimulation from the new life may be all that is required to improve him up to a passable standard. But as a rule, in a new country he finds few to give him a helping hand, and he depends more than at home on the powers within him. I speak with warm feeling on this subject from personal observation in South Africa, at present the fashionable receptacle of our moral waste. I would urge again that self-control, and with it self-reliance, are to be encouraged in our children from the earliest period. We naturally begin by helping them to control their physical or animal habits, and when moral characteristics begin to show themselves, we endeavour to give the oars into the child's own hands, sitting beside him at first to lend him the advantage of our own experience. But "Other's follies teach us not, And we must often be content to watch the child gathering his own experience while we sit in readiness to prevent disaster. It is well to let the child do things for himself as early as possible. Even in trivial affairs, this has a valuable educative influence. The child who can lace up his own boots is ahead of the child whose nurse invariably performs the operation for him; and think of the pleasure and pride the little one takes in doing these little things for himself. He will rush down eagerly to breakfast to tell you he has dressed himself for the first time; and he will tell you with a touch of sadness at lunch that a little friend whom he has met can brush his own hair, while he cannot. Let him be imperfectly dressed at first, and don't mind: if the faults are pointed out he will rapidly rectify them, if he doesn't see them without instruction. These, to us small functions, may often be performed by the child earlier than we think, if only we allow them to try, and are not impatient with early failures. And when he perceives that what he regards as great deeds may be done by himself just a well as by a nurse, he has learnt a great lesson, and will eagerly look forward to the conquering of the next great difficulty. Thus we lead him surely onwards to learn that most things may be done by himself if he tries, and he will obtain control of his habits, physical and moral, all the sooner for these early independent experiments. Those who say "my child cannot sleep in the daytime," or "my child can't take milk," and so on, are not, as they think, referring to an inborn characteristic which cannot be overcome. They are in reality displaying, in nine out of ten cases, their own neglect of their child's early training in habit and self-control. Self-control is an essential element of what we call "manners." What intensely irritating little habits are exhibited by some people simply owing to parental neglect! And how bad-mannered we consider these people. Then, again, nine out of ten of the coughs we hear in churches, theatres and other public places, are simply due to want of attention, want of self-control, a weakness in resisting the impulse to imitate the tenth cough, which may be due to a genuine bronchial catarrh, whose owner has no business to be present. The cheerful word of encouragement should never be omitted. There are parents who habitually depreciate all the independent actions of their children, and even turn them into ridicule. Such children are led to believe that they cannot and never will be able to do anything as well as others can, and this has a notable deterrent effect on the growth of their self-control and self-reliance, the effects of which perhaps may never be outgrown. Reasonable encouragement is valuable. I have spoken of the importance of the personal character of teachers, but just as important is the personal character of the nurse. This is a question I commend for further discussion. Children must be left to their nurses for a greater or lesser part of the day during their early impressionable years of life. The nursemaid, who is the product of board-schools, is not always such as we should desire. If our Union could extend its influence to the lower classes, the effect might be seen amongst nursemaids, and our children would profit. We cannot, unfortunately, all have the benefit of the presence in our nurseries of one of Miss Mason's students from the House of Education. But a course of instruction for girls leaving board-schools and going in for nursery service might well be undertaken by the P.N.E.U. Once more, let me urge that I advocate no scientific precision--no "developing" on rigid lines of a "moral faculty" of self-control. To do so would be to urge the annihilation of the childlikeness of the child--to crush the joyousness of his life. I have simply endeavoured to show that the characteristic grows by exercise of a mechanism possessed by all, and that we parents may well understand something of this mechanism. Self-control is not a crushing of natural desires, or merely the power to conform to custom: to look on it as such is to look on it as a chain to bind us. The man who is master of himself is free. Allow me, in conclusion, to assert that it is false to maintain that lives are shipwrecked morally only by "circumstances"--meaning by a succession of incidents met with over which the individual has had no control. It would be as true to say that a carelessly built, badly found, overloaded, leaking ship sinks in a storm solely because of the storm. Let us pay attention to the fabric of our children and equip them well. Let us not be tinkering nor yet over-nice. Let us launch them manly and robust in mind and body: beings of action rather than creatures of service. When the day comes on which they must leave the harbour we will then send them forth confidently and buoyantly to take advantage of the fair winds, endure the calms, and face the inevitable storms which they will encounter on the seas of life. Even a poor ship may be saved when in difficulties by a competent commander. Make each child captain of himself; give him, before all, self-control. Proofread by LNL, May 2020  |

| Top | Copyright © 2002-2021 AmblesideOnline. All rights reserved. Use of these resources subject to the terms of our License Agreement. | Home |