|

The Parents' ReviewA Monthly Magazine of Home-Training and Culture"Education is an atmosphere, a discipline, a life." ______________________________________ Parents and Masters *

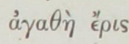

The matter of my paper, which I have named "Parents and Masters," will have been sufficiently forecast by the title. The relations between the parents of a boy and the boy's masters (or if I may have the hardihood to include a topic on which I can speak only by interference from experience, between a girl's parents and the girl's mistresses) are my subject. How these persons think, feel, and act in respect of their joint concern--the education of a child; whether their discharge of mutual duties admits of any improvement; and, if so, in what directions and by what steps improvement should be sought--these questions are the outline of my task. We had better begin, I think, where everything in fact does begin, with the ideal. What is the ideally perfect relation between the parent and the master? Then we will ask how far the actual behaviour of the two falls shorts of the ideal, and through what causes. Last, we will enquire how far the causes of shortcoming can be neutralised or at least reduced. I. Somewhere, though a long way off, there exists--if one may trust Plato, as I heartily do on all really practical serious questions--somewhere in the heaven of ideal forms there exists the idea of the parent and master relation, patiently waiting with a large company of the noblest ideas for realisation in the world of fact. Some glimpse of it is obtainable, as I judge, by any of us who will work out the conception underlying a name by which the modern master is commonly described. The master, we say, is the pro-parent. If that name has been correctly conferred, it will give us, with a little opening out, all that we want. The pro-parent. What the parent has to do for his child, that the master is to do within the time and space limits of his pro-parentship. But what the parent has to do is determined clearly enough by nature, even without reference to a power behind nature. The parent is the protector of the young life with all its interests, present and in the future, material or spiritual, for so long a time as the best evolution of the young life requires such protection. In language more precise as well as nobler, the parent is the trustee of a soul until the soul's pupilage expires. Into this trust he has co-opted a partner; he has made the master his co-trustee of a soul; he divides with him the responsibility for the prosperous evolution of that young life. Some theorists in education complain of the parent for doing this. God, they say, made the family, and made it as the instrument for the bringing up of the child. The family should continue to do its own proper work, not surrender it to that usurper, the modern boarding school. Now the present writer goes a long way, it will be seen, with these theorists, and certainly agrees that God made the family, and made it for this function. But he believes, with the requisite modesty, that God made the school as well as the family, the master as truly as the parent, though not so soon. He thinks then the parent may rightly offer and the master accept this co-trusteeship, and that he rules for their joint conduct of the trust will flow easily and with distinction from the law of that divine institution, the bond of parent and child. Here then is the sketch, as we will venture it, of the relation of parent and pro-parent, as we believe it may be seen in the heaven of the ideals by whoever can get there. All that the parent can do for the future well-being of a child, this (and a little more since otherwise why should the original trustee call in a co-trustee?) the master does for that child, within certain limits of time and space. The time limits are the seven or the nine years spent at the school, retrenched by the fifteen weeks of each year which are retained by the home. The space limits are not, as you might think I meant, the class room, dormitory, and playing field, but the limits of a master's power of penetrating the life of a child who never was his own child and is his in any sense for a season only,--of penetrating the life; I mean, of knowing and dealing with the circumstances, the mind, and the feelings of one who must remain so much a stranger. Within these limits the master undertakes the conduct not of a part of this life (as where the school is a day school or a lecture institution which repudiates all tutelage out of school times), but of the whole,--the health, study, pastime, manners, morals, and religion (if indeed we are to distinguish these last two, as I think we ought not to distinguish them). All these energies of the life he holds in trust. But he is a co-trustee. His colleague, the parent, managed the affairs of the trust before the co-option took place; and though he has become for nine months in the year a sleeping partner in the firm, who asks only fitfully for news of the business, he is in the office again for the other three months, those of the holiday, and presently, when his son is eighteen, will once again be sole trustee. Accordingly our master preserves intact all his colleague's rights, sustains the continuity of the business, and lets no capital be lost in the act of transference to his hands. All good traditions of the family life he guards with jealousy; maintains the authority of the father, the influence of the mother; their lessons in the art of living he reinforces and carries to the further stage: the sense of family honour in the boy he quickens by recognition and by reminder: in particular he fosters the sympathies with home and that mutual knowledge and regard which the nine months' absence threatens, and he is strong on the theory and practice of the Sunday letter home. At the same time he is observing accurately the boy's mental and moral development, its directions, volume, speed, and quality: and he is conveying a picture of this, at critical stages, to the parental mind, so that when the day arrives on which the parent must take up the reins of guidance over an emancipated schoolboy, he may be able to steer the young man both knowledgeably, and with an authority not decayed by abeyance. Thus the schoolmaster was after all rightly named when he was named Pedagogue. The name is of detestable sound, and no man of spirit can be expected to like it, in spite of all the chairs of pedagogy which universities are ambitious to found. But it has an unexpected truth. For the pedagogue, one now remembers, was the man in the humble capacity of a domestic servant, who took the boy safe to the schoolmaster's door and then brought him back safe to the parent's. And just so the true schoolmaster leads the boy from home to school, and--he must lead him back again from school to home; must restore the son, not indeed where the parent left him, but at least where he can overtake him. And the parent--what is that ideal person doing all the time? Before ever he sends him to the school he has taught him a number of things which can best be taught at the home, and for which there may not be time enough at school. He has taught him self-control, because this must be begun early, like the violin. Habits of subordination, because otherwise when he goes to school he will miss his mother who has been his personal servant, when he finds that he is fag to a three years' senior. Good manners, again, so advantageously learnt at home when there are girls, as well as women, whom to know is a liberal education. Religion, too, for which he is never too young, and about which he must not think when he reaches school that it is only a fad of the master's, or at best his mother's, and a thing the "governor" doesn't go in for. Something too he has taught him of the mystery of the human passions, and of their mastery: for though we hope the master will teach him of this, still the master's teaching may come a little too late. There is also a belief in the family honour, of which a master is not the natural teacher; and there is ambition in life, the ambition of being and doing something useful and good, a subject which used to be taken up in the nursery and which cannot well bear the postponement which now is common. All these elements the parent has carefully taught before the child leaves him for school. And, now that he is there, the parent is doing his best to economise the force of that new influence, the schoolmaster. He makes and keeps the boy aware of the reverence he, the parent, entertains for every letter of the school law, even the rules which exclude from the boy's dietary wine and cigars: and he makes the youngster understand that what is frowned on as noxious by the master is not smiled on by the father or mother. Further, he carefully and intelligently acquires the theory of the useful and the good upon which the school has founded its system of discipline and moral teaching, and he never drops the word--or the look--which would apprise the discerning pupil that, in the "governor's" opinion, what the master says is nonsense or only just good enough for use at school. He informs the master in letters without fond partiality and without prolixity, of those traits in his son's idiosyncrasy the knowledge of which is necessary for his right guidance, omitting as idle verbiage the remark that 'my boy can be led but not driven:' and last he is wholly free, like the master, from jealousy of his co-trustee, and only meets him in that rivalry which Pliny calls the [ayadn epis*] --the noble strife, of two friends who provoke one the other to good works upon the character of the boy who is the high concern of both. * These were characters that could not be rendered in html; this is an image of the characters:  This, we have all remembered, is the ideal. It is found in the heaven of ideals, and from that region we must now descend to earth, softly and with as little jolt as possible. II. There are then, let us own, some difficulties when it comes to realising the ideal of the relation between parent and master--this relation so beautiful and of such promise, this co-trusteeship of a soul, fulfilled by mutual confidence, loyal support, intercommunication of the wisdom of the two and a common devotion to the interests of the trust. There are difficulties, and the first is a difficulty of the most general and pervasive character. It is this, that while the relation itself is a spiritual one, the co-operation in a spiritual work, namely, the education of a human spirit, it is associated with, nay, based upon a relation which is not spiritual but practical and commercial. Parent and master are persons who do business together: the schoolmaster is a trader whose wares are instructions in knowledge and behaviour, and the parent is his customer. This business relation would be a difficulty in the way of fulfilling the spiritual relation even if the two were never in a collision, and the performance of the spiritual office were always the business; for the contact of material interests will seem to both parties to taint or at least to make dubious and to dishearten the spiritual effort. But sometimes the two are in conflict, and loyalty to the spiritual duty is not good business. It is possible, for example, in the education market as others, that if the trader refuses to supply the wares which are to his customer's taste, because he believes them to be unwholesome, his customer will leave him. If, to be quite concrete, the master tells the unveiled truth about his boy, perhaps that outraged guardian will take his charge away and place him under some more discerning tutor: or, if he is too wise to do that, will at least burden the master's correspondence-time with an argument conducted through the mails. Here are examples of a difficulty which is real--the confusion worked by the association of moral duty with business. The next is more obvious and more measurable. It is that the day of the best of masters and parents consists of only 24 hours. But the fulfilment of that tutorio-parental office, which we sketched just now with so light a heart, takes a great deal of time. Where in those 24 hours, after providing for the tasks of the ordinary eight working day, is place to be found for those letters, conferences, exhortations, studies of the individual character, and of its changing phases, and crises, and growths, which seem to be called for, if the joint ability of our co-trustees is to exhaust all opportunity of developing the child's nature, and make full proof of their ministry of tendance? Art if long, even the art of educating a soul. When a workman has spent one third, or perhaps something more, of one revolution of this bustling planet upon the indispensables of his task--the lessons and the discipline--he cannot begin the day again just because, if only he did so, some finer finish might be given to that work of his art, the pupil's life. Well, here is another difficulty, the want of time to realise the ideal of joint action of parent and master. Another. Our two trustees often have little trust in their partner, and without mutual trust the best two in the world cannot work together to good effect. Sometimes I suppose the mistrust is well founded. Oftener, as I hope, it is founded only on mutual ignorance. How little do our pair know one of the other! I recall a father (and one of the sort which pays much attention to educational subjects, reads German volumes on paedagogy all day, and lies awake all night thinking that not the best is being done at school for his Julian), and this father, after being asked to meet a headmaster at dinner, complained that the man was not like a headmaster at all; as if headmasters were like anything at all, and not, as the rest of the world, of different sorts and sizes, shapes and colours. But no, my friend had his image of a master, probably something very proud and stiff and forbidding, and heavily gowned, about as like real headmasters as Punch's "John Bull" is like a respectable father of a family, and when he met a gentleman of ordinary and humane appearance he had to correct a preconception. But the ignorance is not one-sided. You may hear for instance schoolmasters, those who are still in their adolescence, talking together over the breakfast table about "the parent," whom not uncommonly they charge with folly. "The parent": as if it were a species, like the lion or the camel or the rhinoceros. These are species, no doubt, and the individuals are one just like another, and you know what he will do, and that if he is a camel he will carry you, and if he is a lion he will eat you. But what a parent will do to you you never can tell merely from his being a parent; it is necessary to know the individual: there is no such thing as the species parent. Well, then, here is a difficulty in the way of fulfilling the master-parent ideal---the two mistrust one another because of their mutual unacquaintance. But perhaps the mistrust which nullifies our co-operation is based not on imperfect mutual knowledge, but on too much knowledge of the partner's defect of wisdom. The writer of this paper cannot so well judge what the parents say about the wisdom of the masters; he is rarely in receipt of their confidences on that subject; but he is aware of what some masters say about the wisdom of the parents, and has heard of one who (this was in the early and omniscient period of his educational career), on learning some recent instance of maternal error, thumped the commonroom table in his heat and exclaimed, with illogical forgetfulness of his own reason for existence as schoolmaster, "Parents have got no business to have children." How could you expect that young man to co-operate with the father and mother in the education of a child whom they have no business to have? No, we need more confidence, each of us, in his partner's wisdom. If I here mention jealousy as a cause of mistrust, I do it rather for the sake of completeness than because I suppose it to be a factor of any importance. It ought, humanly speaking, to be a force; for the parent does seem to risk his or her possession in the love of a child by sending him for three-fourths of his time to the charge of teacher who may win his affections and possible divert some of them from home. But I do not seem to have detected it in any experiences of my own. I have indeed seen it written in the educational journals, that a certain class of mothers, those who have much cash to spare, but are otherwise slenderly endowed with qualities which make children respect their parents, will attempt, to recapture the love of their offspring by the largesse of hampers or of money orders, or of abundant champagne at an Eton and Harrow match picnic lunch. It may be so. But even then the jealousy is not directed at the person of the schoolmaster; the rival here is the school life and other avenues which it opens. Jealousy on the master's part would be a peculiarly monstrous vice, and may be said not to exist. So we may, I believe, rule out this cause of mistrust as quite neglectable. The next difficulty, however, which impedes co-operation is a real one. It is the clash between the ideals of parent and of master. The two trustees are so often aiming in the common business at results which are incompatible, that to do business together is impossible. I will not attempt to say which of the two has the right ideal of a boy's education. Of course it ought to be the master, for it is his profession to think about these things and to advise others, and he has more opportunity of testing his ideals in the way of practice, seeing that his family of boys is at any given moment some score of times larger than a parent's. But, observing that the master as well as the parent has temptations from the side of the world and self-interest, I am only sure that sometimes one is right and sometimes the other. But, unluckily, it is needful that both should be right together. Of the four possible combinations--a good parent and a bad master, or a bad parent and a good master, or neither good, or both--it is only the last combination which secures unity of action, and not always even the last. So true is the hexameter which we remember out of our Aristotle's Ethics, that "there is only one way of going right, many of going wrong." Now it will happen if you have found a well-idealed master, whom nothing will satisfy but a course of discipline which will leave the boy self-controlled, patient, hardy, with an ambition approving things that are more excellent, and a mind which is a perfected instrument for attaining these, that perhaps the boy has a father who doesn't want grand ideas in his boy, but wants "value," meaning the knack of making money in an office, or wants only friends who will be useful to help him presently up a social ladder, or wants for his boy a place in the school football team, and later at the 'Varsity, and as for what the master calls "education," thinks that is only his fun. Or it will happen that you have a wise mother, who knows her boy's constitution and family history, and looking to the whole of life and not a part of it, wants him to develop quietly and without overmuch stimulus and pressure; and a religious mother, who thinks it will not profit her son if he gain a whole world of knowledge, or athletic glory either, and lose his own soul or some of it in doing so; and this wise and religious mother has fallen among masters to whom this son of hers is only a possible scholarship winner, or a possible "blue," and in the one way or the other a tool by which their school is to succeed, and who therefore get all they can and while they can out of his callow wits or half-strung limbs, without regard to the two score and a half of years which he must pass after leaving their school. Here are instances, extreme as I hope and think, but chosen on that very account for the sake of definiteness, of the conflict between ideals of the one partner and the other. Where that conflict exists the partners cannot work together in the common business; there really is no common business. The concert of the two is only a European concert: each does only what the other does not prevent, and so not very much is done between them. But it is time I drew to an end with my string of difficulties which have built up the fact, as contrasted with the ideal, of the parent and master relation. That fact is that the home and school are on the whole in somewhat imperfect co-operation. Each, let us hope, does its best for its temporary charge while it has got him, but does it in its own way, out of its own resources, and discontinuously with the action of the others. The boy whose time is parted between home and school, is managed rather like the child of Ceres, the corn-goddess, who passed half the year with her mother in the sunshine of earth, and half the year with her uncle in the dark somewhere else. I am not putting on my parable more strain of application than it will bear, and I quite decline to settle how we shall distribute the geographical terms of the comparison between us; but I think it must have been very bad for Persephone that the regime on the earth's surface and that under it were so wanting in sympathy and continuity; and I think it will be much better for our boys and our girls (whom I have not been forgetting all the time) if their education in the nine months and in the three could be run on the same lines and with a common purpose by the two sets of educators. So having studied first the ideal and then the fact, we end with the consideration of your third part, the remedies of the fact. III. It will be a convenient method for this consideration if we trace our recent footsteps backward, taking in reverse order the difficulties which hinder us, and attempting their solution. But I think a needful preliminary will be this modest remark--let us not expect too much. It is easy to say, "See how much is lost in education by want of union between the educators! Think, if only the two would pull together as true yoke-fellows, what wonders might be wrought! What a new breed of man might our children become, if only we applied this hitherto unused and unthought-of force, the concert of parent and master! What a new heaven and new earth it might make of home and school!" Ah! but then one remembers that this simple truth can hardly be a new discovery, and if the truth has not energised all these centuries, it must be because some eternal fact prevents it; and one remembers that just those simple little changes in men's practice which would transform human life, are just the little changes which people cannot be got to make. Well, we must be modest, but we will be hopeful too. If then we follow our footsteps backward, the difficulty of the clash of ideals is the first to take. Of this the solution is obvious and also impracticable. Let parent and let master be quite wise and quite unworldly, and they will differ no longer. But as this is asking too much, I suggest instead that the two parties should borrow a hint from the Parents' National Educational Union. They should meet in conference and talk their ideas out together. Thus they will club their wisdoms and cancel their worldinesses, And here remember the special responsibility of the parent for the ideals which shall be set up: of the relation between the two he is the causa causans, for it is he who provides the child and the child's school-fee which are the foundation of their union. It is he therefore who has the call. Besides, though I have maintained already that the school as well as the home is a work of God, still the family was earlier made to be the educator of youth, and the native methods of the family are, in my thinking, the example which the school should follow; therefore paterfamilias is really and by nature's plan the expert of the two, unless the master himself happens to be, as I hold it better to be, a paterfamilias also. Pending, however, this proposed conference of educators, one or two suggestions may be offered at once, because no conference will be able to deride them. First then, let us both, parent and master, cure ourselves of that false ideal which I will call the athletic craze. I say "both," but only out of modesty: for, really, and in spite of popular notions, it happens to be a parent's craze not a master's. Masters do not award too much time to it, and they do not overestimate the value of games. If they do, it is because the parents make them. While parents judge of schools by the successes won by the boys' muscles and lungs (which grave observers tell me is the case, for I know it only at second hand), and while boys think (which I know at first-hand of some) that their fathers would rather see them in the "fifteen" than in the "sixth," * your human master will be much tempted to provide what his clientele most fancies. And let us cure ourselves of another false ideal, the social craze. A good many years ago one heard it said of a well-known school, "It is a fight between Blankton and Education, and I believe Blankton will win." But the reason why the Blanktons win against educational reform, if they do win, is that the parents do not so much desire educational reform as to be ready to forego the alleged social advantages of the unreformable so a system of impossibly large classes, in which a teacher cannot get round his work, is tolerated, because if Henry learns less grammar he will make more friends. And let us cure ourselves of one more ideal, the "bread and butter" one. Let us not have the teacher appealing to the pupil to perceive the charm and the discipline of the humanities, and the father telling him that nothing he learns at school is any use except the book-keeping, for that when he joins the business he will find none of the clerks or office-boys will talk Latin with him, if he wanted it. That forlorn teacher has been in a quiet conference trying to make a rather dull modern-sider believe that though he never will be a Latin scholar at the end of it, yet every ounce of honest effort which he has put into the mastery of a sentence in Livy, will be paid him back, not in elegant scholarship, but in the grit and quality of mind which will make him the mysterious better and natural lord of the clerks who can only do sums. In vain; his father is in business, so he knows; and he says book-keeping is the thing, and Latin is rubbish. Let us rid ourselves of this false ideal too. * [There are fifteen players on a Rugby team; sixth may refer to moving up to the Sixth Form.] But then, is it enough for us to get rid of ideals that clash? Each of the boy's teachers, the man at the school and the man or the woman in the home, should also give a positive support to the right ideals of the other one. If they do not, there will be much waste and leakage of moral force. Our younger pro-parent, the one who holds that "parents have got no business to have children," must learn to work upon his pro-children by an appeal to the family sentiment. He must know a little more than at present he remembers of the way life is looked at from beside the hearth; must remember that love of father and mother, sister, and even brother, are real human affections, and can be utilised as forces upon the boy's nature; that ambitions for a true success in life are being inculcated by the mother in a holiday talk, as well as by himself in his school sermon or admonition in his study. He must not ignore these influences, or let the boy think he ignores them; nay, he would do well to speak as if he assumed their assistance, even though he has not verified it. On the other side the real parent cannot wisely remain ignorant of the schoolmaster's ideals. These may seem to his experienced business self to be unpractical, superfluous, fanciful--briefly, "fads." But, even supposing he is right, he had better not let his son know it. That youngster's heart has perhaps come under the spell of those superfluous notions, or of the personality which he feels to be behind them, and the spell is doing him no harm, even if some day it will melt; a year or two of romance will not spoil him for business presently, and meanwhile is making a better fellow of him. Now, if he should hear his father over the breakfast refer to his master's little peculiarities of theory of management with that tone of sad or genial tolerance with which at that meal we discuss, say, our parish clergyman, one or two ill-consequences will ensue; either the father will have clothed his already impenetrable offspring in a new armour of scepticism against the master's moral assaults; or, if the boy is already on the master's side, he has warned his son not to come to his father for sympathy on the things which just now he cares about most of all. That is the boy's loss, but is it not the father's too? What has he not thrown away? After considerations so delicate as these last, one can hardly without shock descend upon such details as the following--that school laws should not be broken by the home; forbidden comestibles should not be sent in hampers; the rules about exeats and return to school should be loyally kept, if only not to teach a boy lawlessness; and while boys are not allowed to smoke in term time they should not be allowed to smoke in holiday time, if only because a parent ought not to be a child's tempter and make self-control too difficult. We must hurry on backwards and find a word to say on the next cause which dissevers parent and pro-parent--mistrust. So far as this is based on mutual grievance, the cure is obvious--know one another. Let the parent not fail to visit the school and meet his boy's master in the flesh. It makes such a difference. I recall the first days of a young master of a boarding house. He got in his first term a grumble in five lines of note paper about a boy's clothes, and thought what a disagreeable, conceited fellow this is, he wants to be put in his place; which operation he essayed by return of post. Well then, five weeks later drops into tea and a stroll round the garden a quite charming old gentleman, whom he was reluctant to let go off the place again; and this old gentleman was the author of the letter. Now supposing that their little brush had been not over the boy's clothes, but his character, what a pity the mistake would have been! However not all the failure of mutual trust is due to ignorance. Sometimes it is well based; they do not trust each other because one or the other is not wise, or is not unselfish, because the parent won't stand blame of his son, or the master won't stand blame of himself, because the parent thinks only of the boy's interest and the master only of the school's. To be brief, they do not trust, because they cannot trust. The cure is not ready. What we had better recommend is that the mutual trustfulness should be provisional and proportional and progressive--a stately formula which only means that a partner must feel his way, must in the bestowal of confidence give the other as much of it as he can carry and not more, and must always aim at increasing the load as fast as his partner's capacity is verified. Each will do well to believe, that the degree of confidence he gives to or gets from his partner depends largely on his own conduct. Someone has said that a people generally gets the government it deserves: let us say that a parent gets the masters he deserves, and a master gets the parents. And now we have run up against that most solid of obstacles to a common management of their joint affair by our two--that there are only 24 hours in a master's day, and no more in the parent's. The latter, when he comes home from his bank or practice, and finds the educational impulse in him tamed by the day's fatigues, will understand how the master after paying out a day's energy in tutoring this banker's son, is not inclined to spend it over again by correspondence on the subject with that financier. An older contemporary of mine, who was a housemaster at a great school, must have allowed this elemental fact to escape him, for he wrote an article on school in a leading monthly, in which he exhorted the parents to "bombard the schoolmaster with letters." This gentleman was I think one of that class of men so dangerous to society, the philanthropists; and like the rest of them he went to find his brothers a long way outside his own family circle. A more unfraternal counsel was never given, or a more mistaken one. Had that article been held back till a war in South Africa had been developed, the writer would have known more about the futility of bombardments. They have, whether applied to a Boer or a schoolmaster Briton, only one effect; they never increase the activity of the bombarded forces; they only make them lie low and keep out of the way till it's over, or till Sunday comes, and there is no delivery of shells or letters. No, I don't think we had better stimulate the jaded energies of the schoolmaster with bombs. I should be inclined to advise that these limitations of time are the decree of nature and much must be submitted to; but also that nature is a very wise goddess, and very possibly the narrow margin of time, which she has allotted for consultation between school and home, is just exactly the amount which can usefully be spent upon that operation; that, to be more precise, the master had better write only when there is something to say, which will only be now and then, when a crisis or a half-term report has arrived, and that, for so much as this, opportunity is not denied him. Further, I should advise that a school is, or else ought to be, only a very big family, and that as far as I can see, the big families, where the mother has least time for each child's affairs, do somehow bring the children up as well as homes where all the pains can be concentrated on one. And now we are under the very goal of our enquiry. There is but one difficulty left of those which we proposed, if we could, to remedy. It is the difficulty that this relation of our co-trustees, which is itself a spiritual relation, is based upon a connection which is material, that of the market, of buyers and sellers, a relation which is unspiritual and of the world. Is that a difficulty at all? Is it not rather an opportunity? For how does the case of the spiritual in the world differ here from its case everywhere? From the one end of things to the other the spectacle is that of spirit tied to a reluctant matter, and seeking to absorb that matter into itself. All human nature is one vast sacrament of this union of the ideal with the actual, of spirit with flesh, And everywhere too one perceives a law, obscure and hard to formulate, by which what seemed limitation and hindrance proves the very means of the victory of spirit. Life then is such. And we co-trustees of a soul have for our special action in this world-battle of spirit and flesh, the task of spiritualising this relation which is ours, of getting the Promethean spark of love into the clay of business. We will not murmur at the difficulty: we will count it all joy. And we teachers in the home and the school will recall as a happy omen for our joint task, that we are bound together in a mutual duty by the child. The child was ever the world's sanctifier. When the old-world thinker foresaw a day of the victory of the ideal, in which the gross nature-struggle would be quieted under a reign of peace, he pictured the transformation as a paradise in which the primal, wild, conflicting forces of human existence, the self-interests, greeds, ambitions, rivalries, passions--the wolf, the leopard, the bear, the lion--would be in conflict no longer,--and a little child shall lead them. *As an act of respect to the Parents' Educational Union, the writer desires to say that if some of the thoughts and illustrations of this paper should be traced in a recent book (Pastor Agnorum) by the same writer, the charge of plagiarism does not lie against the paper, which was written before the publication of the book. To be continued. Typed by happi, Mar 2020; Proofread by LNL, Apr 2020 |

| Top | Copyright © 2002-2021 AmblesideOnline. All rights reserved. Use of these resources subject to the terms of our License Agreement. | Home |